The Renaissance Man: The Case for a Liberal Arts Education

And why we need one more than ever before

“...the ability to make connections across disciplines—arts and sciences, humanities and technology—is a key to innovation, imagination, and genius.”

— Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson

Leonardo

There are few, if any, who rival Leonardo da Vinci in curiosity—or historical celebrity. The Italian painter, architect, inventor, engineer, sculptor, and intellectual is perhaps the greatest thinker humankind has, and possibly will, ever produce. There have been other illustrious painters, more accomplished engineers, and sculptors who surpass Leo in skill. And yet, if I were to ask anyone in Times Square, Istanbul, or anywhere else to name a painting, 9 out of 10 times they would respond with The Mona Lisa. Not Rembrandt’s NightWatch or Klimt’s The Kiss. Not even Picasso’s Guernica, the Spaniard’s tour de force. “That woman by Leonardo da Vinci,” they would say, “the one in Paris.”

Why, then, centuries after his death, are we still collectively obsessed with the Renaissance man? What distinguishes da Vinci and renders his work irresistible to the millions of tourists who take a pilgrimage to the Louvre? Simply put, it is his insatiable appetite for knowledge. His obsession with uncovering the divine workings and language of our enigmatic world. Leonardo was propelled by pure, childlike wonder. It is that awe, that inescapable sense of reverence in da Vinci’s strokes that sets him apart.

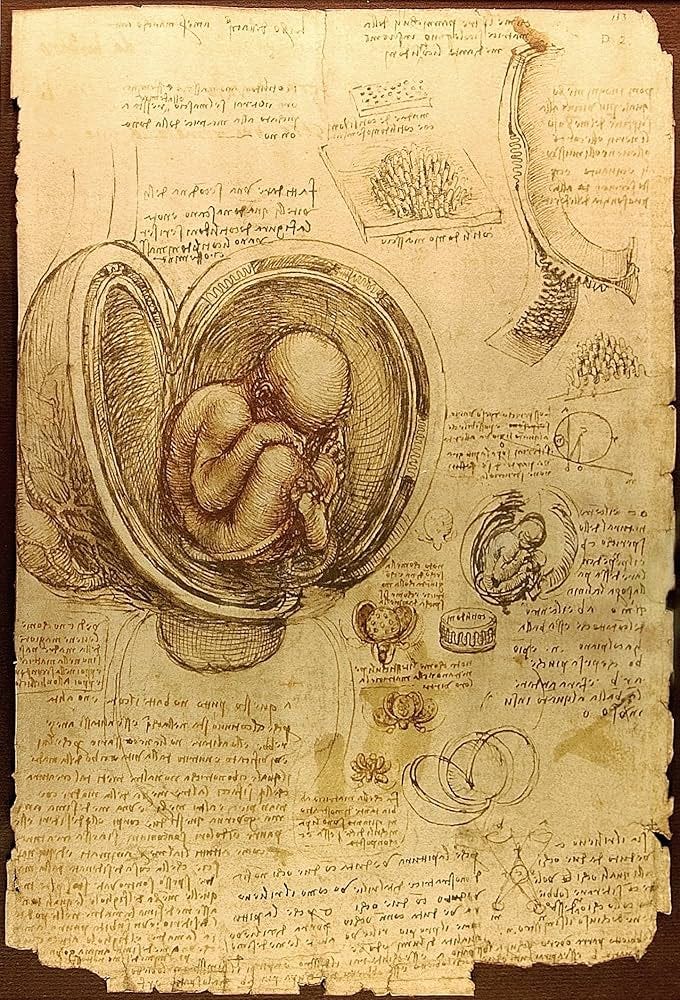

Leonardo’s genius is nowhere more evident than in his notebooks, where da Vinci drew elaborate, anatomically accurate diagrams and scribbled questions. Analyzing his notebooks is the closest we will ever get to understanding his mind. What quickly becomes clear to the reader is da Vinci’s commitment to interdisciplinary thinking. Plans for a flying machine are drawn and described alongside exquisitely rendered human exoskeletal systems. Questions about a woodpecker’s tongue, adjacent to sketches for an upcoming painting. His imagination thrived in the connections between the objects of his curiosity, rather than in hyperfixation on a single field of interest.

In Leonardo’s paintings, his interdisciplinary thinking is front and center. For instance, his use of proportions and perfect curls is inspired by his study of mathematics and physics. Even the plays he would put on for the Sforza court in Milan were built on contraptions he devised using his engineering skills. Da Vinci’s scientific knowledge was at the foundation of his artistic creation, and his artistic creativity in turn inspired his scientific inquiry. Da Vinci’s rejection of specialization was his greatest strength. The same will be true for the leaders of the next generation.

The Liberal Arts & AI

In the past century, to the delight of some and the dismay of many, training in the liberal arts has become a hallmark of American higher education. The widespread adoption of the ancient Greek approach has presented some obvious questions: A first-year Economics major at Columbia, on his way to Literature Humanities, may question why he should bother reading “books that enable us to ask questions about literature and how it works,” when he plans to land a job on Wall Street upon graduation. Wouldn’t cramming his schedule with advanced courses on the working of the market seem like a better use of his time? Why, then, do top universities with thousands of notable alumni go to great lengths to ensure pre-meds take history and archeologists take calculus?

The answer lies in the value of interdisciplinary thinking and flexible problem-solving. In the age of artificial intelligence, where technology can crunch numbers and generate code faster and of higher quality than the average white-collar employee, specialization has lost its allure. Instead, we must channel our inner Leonardos and embrace creativity. Fundamentally, LLMs are plausibility engines, designed to spit out the most probable response to a query. The one thing these chatbots cannot do, by definition, is iterate beyond the data they have been fed. As students globally use artificial intelligence to write their essays and brainstorm, a generation that is incapable of critical thinking is entering the workforce.

We are hurtling towards a world where AI outages could spell disaster for productivity. Automation will infiltrate every facet of our society, providing subpar replacements for human output. But because Chat-GPT or Grok will never be able to innovate, the last human frontier will remain originality. To optimize for this new reality, we will need to adjust our academic incentive structures to provide students with the necessary background to be as original as possible. In human employees, ingenuity is becoming significantly more valuable than efficiency.

American Universities

And yet, around the world, top universities outside the US still insist on pigeonholing students into a particular course of study. In England, renowned for its academic institutions, universities such as Oxford and Cambridge often require students to specialize within their fields. Some argue that intense concentration on a narrow field for three years produces more desirable, highly skilled employees. And that may well be the case in STEM, where specialized knowledge is essential. However, for the vast majority of students seeking higher-level education, especially at elite institutions, it is vital that they cast a wider intellectual net.

In the United States, our universities have not become the envy of the world for hiring the best academics. They enjoy universal prestige for creating an intellectual environment conducive to creativity. Great American ideas that reshape industries do not originate from staying within a field. Instead, they are formulated by the joint effort of those working in disparate areas willing to synthesize different ways of thinking. Innovation is a product of the cross-field inspirations that Leonardo relied on. Steve Jobs, in particular, is a great example. Courses he took on calligraphy at Reed inspired his beautiful engineering approach to product design. Elegant exteriors combined with robust electric interiors have defined the Apple brand. Jobs found success at the intersection of art and engineering. However, without having had the exposure to those university-level courses, he may never have been able to design the iPhone.

Conclusion

It is a tragedy that tens of thousands of the brightest minds reject the arts and humanities, choosing instead to focus all their attention on a single, specialized STEM-oriented skill set. We do not need more computer scientists or investment bankers. What we need is minds primed by a liberal arts education to make connections and push the boundaries of what is possible.